Each year, the Council on East Asian Studies awards grants to Yale University students for language study and research related to the study of East Asia.

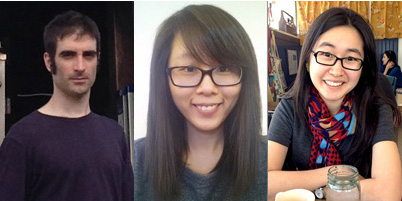

Yale Ph.D students Rea Amit (FILM/EALL), Lan Jin (F&ES), and Alyssa Paredes (ANTH), were among 2014’s CEAS grant award winners, and we recently caught up with them to ask about their summer experiences.

Rea Amit (FILM/EALL)

Rea Amit (FILM/EALL) received a CEAS Field Research Grant to help support six weeks of research in Japan for his project, “The Golden Age of Japanese Cinema, the Nation and the Everyday.”

To begin, could you please provide a brief summary of your research?

My research examined broad discourses on popular cinema in Japan during the late 1950s and early 1960s. Since popular cinema was not often discussed by critics (they widely dismissed it as kitsch), my attention was given primarily to publications by non-professional writers, random accounts by frequent filmgoers, and to individual fans.

How did you first get interested in your topic of research?

I realized that there is a gap between the image of Japanese cinema and what Japanese were actually watching; particularly during the third decade of the Showa era (1955-1965). Given that this was a time when more films were produced in Japan than anywhere else in the world, I felt that there is a pending need to expose this lesser studied phenomenon, and to elaborate on issues with regard to the discrepancy between the aesthetic of an image of a national cinema and the reality of everyday filmgoers at a given time and place.

What did you do for your summer project?

Since information on non-artistic, popular film culture is very difficult to obtain, I had to comb general popular magazines, hoping to find published letters by readers, advertisements, and rare articles, or even partial references to popular cinema. Among the many publications I carefully studied are weekly magazines (shūkanshi) such as: Heibon, Asahi, Taishū, News tokuhō, Josei seben, Shin shūkan, Jitsuwa yomimono, Terebi jidai, fūfu, Jitsuwa to hiroku, Jiji, Modan Nihon, Gendai, Kōron, Shōnen magajin, and Bunshun. These are available for researchers mainly at the National Diet Library, and the Oya Sōichi archive. In addition, at Waseda University’s Tsubouchi Memorial Theatre Museum library, I looked at newsletters and publication by the some of the big film studios at the time such as: Shōchiku gurafu, Daiei gurafu, and Tōhō, but most of my attention was given to Tōei’s fan club magazine, Tōei no tomo. Finally, I also sent out questionnaires to about 350 former film fans.

What would you say were the most interesting findings of your summer research? Were there any surprises?

I was surprised to find out (although this cannot be statistically proven) that so many fans of Toei, a studio chiefly known for its jidaigeki (period drama), were actually young women. Also, unlike what is normally thought about film stars, I was surprised to find out how relatively approachable they were for fans.

What was the most challenging part of your summer research? Were you able to overcome these challenges?

With the exception of the scarcity of publications from the time period that deal directly with popular cinema, as well as the long hours I had to spend at gloomy archives, I cannot really single out any particular challenge that I had to overcome.

Now that you are back on campus, what is the next step for your research?

Making sense of all the stuff I have collected over the summer! I have literally hundreds of different pieces of information, some statistical data, and dozens of fan letters, from which I need to extrapolate a larger statement about what cinema culture at the time really was, as well as to come up with a theoretical framework in which to put this as a broader statement about an aesthetic of Japanese cinema.

Do you have any words of advice for graduate students who plan to do research abroad next summer?

Arrive at archives first thing in the morning, and try to gather as many documents as possible while there. Before you go, however, make sure these are not available at Yale or through borrow direct.

Lan Jin (F&ES)

Lan Jin (F&ES) received a CEAS Summer Travel & Research Grant to support 2 months of research in China. The title of her project was, “Proximity to Heavy Traffic and Congenital Heart Defects in Lanzhou.”

To see photos from her research trip, click here.

To begin, could you please provide a brief summary of your research?

My research focuses on the health impacts of air pollution, especially for susceptible populations in less developed countries and areas. In my current project, I am investigating the relationship between maternal exposures to air pollution and congenital heart defects (CHD) in Lanzhou, China. I am also interested in the interaction between air pollution and social factors, including social economic status and lifestyle choices, and how these factors modified the impacts of air pollution on human health.

How did you first get interested in your topic of research?

Air pollution is the ninth risk factor of global disease burden. Globally, ambient particulate matter pollution accounted for 3.1 million deaths and 3.1% of disability-adjusted life years from 1990-2010. However, some countries and areas disproportionately experience high levels of air pollution and this disparity is increasing over time. Air pollution has been linked to numerous health outcomes, including cardiovascular, respiratory disease, and adverse birth outcomes. As extreme air pollution events have increased in China in recent years, Chinese people, as well as foreign talents living in China, are concerned about their and their children’s health. CHD is the most prevalent type of birth defects globally, and its prevalence is highest in Asia, where no studies have been done to investigate the impacts of air pollution on CHD. In addition, both air pollution exposures and health outcomes are influenced by many social factors, such as education, income, urbanicity, and occupation. Therefore, it is important to identify, quantify, and control for these factors in order to study the health impacts of air pollution.

What did you do for your summer project?

I focused on one pollution source—traffic pollution—this summer, after I found air pollution exposures estimated using monitoring data were significantly associated with increased risk of CHD risk in a birth cohort in Lanzhou, China. This birth cohort was directed by Professor Yawei Zhang at the Yale School of Public Health. There are two parts in my summer project. The first part is to construct a horizontal profile measurement of traffic pollution to depict the dispersion pattern of pollution from roads. I conducted measurements at different distances to a major road for seven days continuously. Three pollutants were measured: black carbon (BC), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), and particles with diameter no more than 10µm (PM10).

The second part of my project is to link traffic pollution to CHD. In this pilot study, I randomly selected 40 births (20 cases and 20 controls) who were born from 2010-2012 in the largest hospital in Lanzhou, China. I visited their residence at birth (outside the buildings) twice to conduct measurements of the above three pollutants. Then, I did a statistical analysis to see whether or not there was an association between traffic pollution levels at their residence and the CHD risk. Because the small sample size in the pilot study, I could not control for the social factors of the mothers that have been collected in our previous study.

What would you say were the most interesting findings of your summer research? Were there any surprises?

I found that NO2 and BC concentrations, surrogates of traffic pollution, decayed linearly first and reached a plateau at about 100m from the major road. This is consistent with previous studies conducted in other countries. The concentrations of BC, NO2, and PM10 for the cases were all higher than the concentrations for the controls. Even though not statistically significant, the absolute difference is relatively large. The associations of NO2 and PM10 with CHD were marginally significant. Each 10µg/m3 increment, NO2 and PM10 exposures were associated with 16% and 3% increase in the risk of CHD, respectively. The results were consistent with previous studies or our expectations.

What was the most challenging part of your summer research? Were you able to overcome these challenges?

One most inconvenient logistic challenge was that one of my instruments purchased from a company in New Zealand was held up by Chinese Customs when it was shipped from New Zealand to Lanzhou city. The equipment was considered as a sensitive object because they thought this equipment was imported as a company sample to be sold in China. I contacted Chinese Customs and Fedex multiple times, and filled out a lot of paperwork to file a claim for the equipment. After waiting a whole week and paying tax, I finally received my equipment. I was able to finish almost all the measurements that I planned.

Another challenge was collecting traffic data from the local government. Vector road maps (used in ArcGIS) are considered as confidential information in China and they are extremely expensive (about $80,000 per km2). The original plan was to use the distance between residence and major roads to estimate the exposures. Because it was impossible to purchase an official road map from the government, I selected a random sample from our cohort to measure traffic pollution at residence to do the above analysis.

Now that you are back on campus, what is the next step for your research?

Now I am trying to use open street maps to estimate the proximity to major roads from residence. The accuracy and completeness of open street maps in developing countries are uncertain. I will do more work to test the validity of using open street maps in the exposure assessment. Then the exposures of all the eligible births in our cohort will be included in our models to give more statistic power to our results.

Do you have any words of advice for graduate students who plan to do research abroad next summer?

I would suggest that they do as much preparation as possible. Even though you might be fully prepared, there are always some unexpected situations in the field. Detailed plans, such as housing, transportation, and work, should be made in advance if possible. Bring equipment with you as personal belongings. Once they are held up by Customs, you have to pay tax and do a lot of paperwork to get them back.

Alyssa Paredes (ANTH)

Alyssa Paredes (ANTH) received a CEAS Summer Travel & Research Grant and a Charles Kao Fund Research Grant to help support her summer project, “Artisanal Production and Alternative Economies in Inter-Asian Fair Trade Networks.” Alyssa also received a CEAS Summer Language Mini-Grant to participate in the Kyoto Consortium for Japanese Studies (KCJS) summer intensive Japanese language study program at Doshisha University.

To begin, could you please provide a brief summary of your research?

Broadly speaking, I’m interested in the relationship between “alternative economies” and the “mainstream market.” For my Ph.D. research, I am planning on doing an ethnographic commodity chain study following an Alternative Trade Organization’s trade in Philippine balangon banana from its production sites on Negros Island in the Philippines, to its consumption sites in the neighborhoods of urban Japan. I am curious to find out about how conscious consumers in Japan are partnering with small-scale producers in the Philippines to operationalize their visions of an “alternative economy” under the pressures of free market agreements proposed by the Trans-Pacific Partnership and the 2015 ASEAN integration. I am interested in the balangon banana specifically because it is a wild Cavendish cultivar with characteristic biological properties that limit its cultivation to bio-diverse settings, making it uniquely resistant to mono-crop plantation.

How did you first get interested in your topic of research?

My interest in this particular trade network is actually an offshoot of a much more longstanding interest I’ve had in the lives of small-scale producers. I started making pottery as an undergraduate at the University of Virginia, and I did a Fulbright project from 2011-2012 conducting fieldwork in two important folkcraft villages in Southwestern Japan called Onta and Koishiwara. While there, it became apparent to me that despite the villages’ relative geographic isolation and the small volumes of their production, they were very much involved in larger global networks, both of objects and ideas. The potters were sending their products around Japan and all the way to Europe, and they were also actively grappling with the philosophies of folkcraft idealist movements around the globe.

For my graduate studies, I thought it would be fascinating to deepen and lengthen my ethnographic work to include not only the methods of production, but also of transportation and consumption - in essence, the entire commodity chain. As someone who grew up in the Philippines, I became personally invested in thinking about producer and consumer relationships between Japan and the Philippines in particular.

What did you do for your summer project?

With support from the Yale Council on East Asian Studies, I spent four months over the last summer doing preliminary exploratory fieldwork and advanced language training in Japan and the Philippines. I dedicated most of my fieldwork to mapping out the trade networks of Alternative Trade Organizations (ATO’s) between the two countries. This meant a couple of things: figuring out who were the major organizations involved, what were the major commodities being imported and exported, and how/when partnerships had formed between Japanese consumers and intermediaries and Filipino producers. These explorations took me from urban Manila, to the rural outskirts of Negros Island, to the cities and suburbs of Kyoto and the larger Tokyo/Kanagawa region.

Halfway through the summer, I participated in the Kyoto Consortium for Japanese Studies at Doshisha University, where I took advanced Japanese language classes, did some original research with Japanese texts, and participated in a couple of student organizations dedicated to promoting alternative forms of trade like Fair-Trade.

I ended my summer by attending the International Institute for Asian Studies’ Summer School in Chiang Mai, Thailand for two weeks. I had the chance to meet scholars, policy-makers and practitioners interested in the central theme of “Reading Craft: Itineraries of Culture, Knowledge and Power in the Global Ecumene.” This was a wonderful opportunity to think through some of my earlier ethnographic work with Japanese potters, and consider the role of small-scale producers in large global trade networks more broadly.

What would you say were the most interesting findings of your summer research? Were there any surprises?

I was surprised by the ubiquitous Japanese presence when I traveled to Negros Island, known as the “Sugar Capital of the Philippines.” From NGO workers and medium-sized enterprises, to tour groups and student volunteers, a diverse assembly of Japanese people seemed to be drawn to, if not invested in, this rural Philippine island, for reasons of which I was not initially aware. I spent a significant part of my summer fieldwork trying to delve deeper into this history of Japanese involvement in the Philippines, and found out about a fascinating story harkening back to the 1970’s and 1980’s period of radical Leftist activism in response to the Vietnam War, the Philippine Marcos presidency, and the world sugar crisis that hit Negros, a “one crop economy” in sugar cane, especially hard. I am planning to continue this research for my Ph.D. dissertation.

What was the most challenging part of your summer research? Were you able to overcome these challenges?

I found that one of the more challenging things this summer was directing all my attention and energy to my language study program at the Kyoto Consortium for Japanese Studies. For the two months that I was enrolled at KCJS in Kyoto, there was constant temptation to get my homework done quickly and continue doing exploratory work for my fieldwork project. The Ph.D. program at Yale often does not allow room for taking a language course while on campus, so it was crucial that I really focus on advanced language acquisition while the opportunity was available. I found a happy compromise by using homework assignments and class projects, where appropriate, to practice drafting introductory letters, “Thank you” letters, interview questions, and the like, in Japanese with the support of my language instructors. For my final presentation and research project, I did a directed reading session on a topic relevant to my research.

Now that you are back on campus, what is the next step for your research?

Now that I am back at Yale, I’m looking forward to spending some time gathering my thoughts and reflecting on the directions that this research project could potentially take. I am enjoying incorporating some of the questions that came up from my summer fieldwork into the broader themes I’m exploring through coursework in Anthropology. I collected quite a bit of reading material in Japan and the Philippines, and I’m excited to dive into those literatures, especially as I begin to prepare grant proposals and research prospectuses for the near future. Practically speaking, I am hoping to start some tutoring through the DILS program in Ilonggo/Hiligaynon, a Philippine Visayan dialect spoken on Negros Island, where I hope to continue doing fieldwork.

Do you have any words of advice for graduate students who plan to do research abroad next summer?

I found it very helpful to begin making some research connections and setting up interview appointments before leaving for the field. I realized that between fieldwork and language study, the time available for meeting potential research informants would be scarce and, therefore, precious. Knowing that it can take several weeks to arrange meetings, I sent out some emails introducing myself to individuals and organizations I was interested in getting to know further. I attached a concise and clearly written one-page summary of my project ideas, goals, methods, and ethical considerations (IRB-related matters), in case they were interested in knowing more about my research. I was very pleasantly surprised at the hospitality I received in response. After every conversation, I made sure to ask if there might be anyone else with whom they thought I could speak, and I used those connections to expand the network.

All that said, serendipity is a very important part to fieldwork, no matter where one works in the world. While being prepared and purposive can make for a productive experience, I think it is equally, if not more, important to always be open to new directions in response to whatever you experience on the ground.

Information about CEAS grant opportunities can be found on the academics section of our website.

Applications for 2014-2015 CEAS grants are now available on the Yale University Student Grants & Fellowships Database. Application deadline is February 13, 2015.